On 22 April, militants from Pakistan-backed Lashkar-e-Taiba’s (LeT) proxy The Resistance Front gunned down 25 Indian civilians in Kashmir. On May 7, 2025, India responded with "Operation Sindoor," a series of coordinated military strikes targeting terrorist infrastructure within Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Later on the same day, a Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson shared that they find India’s military operation "regrettable", providing a calibrated diplomatic rebuke to signal China's continued strategic hedging between counterterrorism discourse and its enduring “all weather” alliance with “iron-clad” friend Pakistan.

China’s response casts a shadow over its self-ascribed role as a leader of the Global South as well as an aspiring peace-broker in regional conflicts. By characterizing India’s counterterrorism operation as “regrettable” –while remaining silent on the massacre of Indian civilians on Indian soil by Pakistani-backed terrorists –reveals the asymmetries in its normative commitments. Diplomatically shielding Pakistan not only undermines its credibility as an impartial negotiator but also exposes the limits of China’s ‘neutrality’ in South Asian crises –a pattern increasingly at odds with its declared ambitions for global leadership and conflict mediation.

To understand the layered nature of China’s response, it is critical to look beyond the statements made by the foreign ministry and instead examine the broader ecosystem shaping Beijing’s regional posture. From diplomatic engagements with Islamabad –such as Wang Yi’s call with Pakistan’s Foreign Minister calling for “impartial investigation” on the terror attack and the Chinese ambassador’s meeting with Pakistan’s Prime Minister reaffirming the latter's “legitimate security concerns” – to the strategic framing of events in Chinese state media, and the silences and tactical narratives circulating on social platforms, China’s handling of the Pahalgam killings and Operation Sindoor reveal the contours of a complex balancing act. This act is not merely rhetorical, but instead reflects a deeper strategic calculation, wherein Beijing seeks to protect its stake in Pakistan while managing regional optics.

Notably, some strands of the Chinese commentary subtly draw parallels between India’s assertiveness along the Line of Control (LoC) and its behaviour along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), hinting at enduring strategic distrust of India despite the October 2024 border agreement post Galwan 2020. China’s choices are informed not just by loyalty to Pakistan, but also by a growing awareness that its investments, including the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), cannot remain insulated from instability emanating from cross-border militancy.

Through Thick and Terrorism: A true ‘All Weather’ Alliance

In the aftermath of Pahalgam, India’s Prime Minister Modi received calls of support from leaders of the US, France, Israel, Egypt and more; China, notoriously, was missing from this. Post Operation Sindoor, an initial Xinhua article reported neutrally about the details of the Operation conducted by citing official sources from India and Pakistan. However, another Xinhua report –published in Chinese– furthered Pakistan’s narrative of playing the victim card by focusing on casualties of India’s airstrikes. This dichotomy aims to subtly shape anti-India narratives domestically within China and at the same time, promote its image as a benign non-interventionist power at the global level. India for its part has adhered to diplomatic protocols with India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval briefing his counterparts across countries, including China’s Wang Yi, on Operation Sindoor.

Beyond the reports published by Chinese state media, analysis of Chinese commentaries on this issue also reveals a popular theme of promoting Pakistan’s side and discrediting India’s position in this crisis. One common thread among many Chinese experts is the fear of escalating the India-Pakistan crisis into a nuclear war, and thus urging other countries to intervene diplomatically to avoid further escalation. While China is likely to refrain from getting directly involved in the conflict, it would prefer getting more global attention on this issue so as to complicate matters for India diplomatically.

In alignment with the pro-Pakistan narrative run by Chinese official media, even social media has witnessed active discussions promoting the same narrative by blaming India for this crisis. Many accounts have been propagating unverified stories about India’s loss of fighter jets, while some have accused India of escalating tensions by violating the water treaty. This has also given rise to several rumours on platforms like Weibo about capture of some Indian soldiers by Pakistan, aiming to malign India’s image and support China’s all-weather strategic friend.

Several Chinese media reports also attempted to undermine India’s preparedness to conduct retaliatory attacks against Pakistan. Until Operation Sindoor, some Chinese commentaries had been spreading misinformation about India’s so-called “humiliation’ during the 2019 Balakot air strikes, suggesting that any similar attack would again expose operational inefficiency of the Indian Air Force despite the improvement in terms of fleet size. Some experts have also linked India’s blaming of Pakistan for the Pahalgam attack to India’s own economic and religious instability concurrently attempting to also challenge India’s position on other bilateral issues including the India-China conflict.

There is also a popular view among Chinese commentators that besides targeting “terrorist infrastructure" in Pakistan, the aim of Operation Sindoor was also to weaken Pakistan’s regional status and expand India’s influence in South Asia against China’s rise. This indicates China’s concerns regarding its engagements not only in Pakistan, but throughout South Asia as the region continues to remain unstable, complicating the geopolitical dynamics. In this regard, one unverified report also dissected the reasons behind India’s refusal to accept an alleged “mediation proposal” by Beijing, which if true, would still be completely within Indian jurisdiction and strategic autonomy to do. Thus, while supporting Pakistan at different levels, China remains eager to use the current situation along LoC to push narratives around its image as a global mediator.

Price of Patronage?

For all of China’s proclamations of neutrality and conflict resolution, it has a permissive attitude in dealings with Pakistan when it comes to cross-border terrorism. This reveals a dangerous paradox: strategic indulgence now threatens China’s own long-term interests in the region. By refusing to censure Islamabad in the wake of Pahalgam –and with continued heavy mortar shelling by Pakistan along LoC in forward areas like Pooch and Rajouri post Operation Sindoor –Beijing’s success in shielding its “iron” brother Pakistan is momentary. It comes at the cost of jeopardizing China’s regional credibility, economic stakes and internal security.

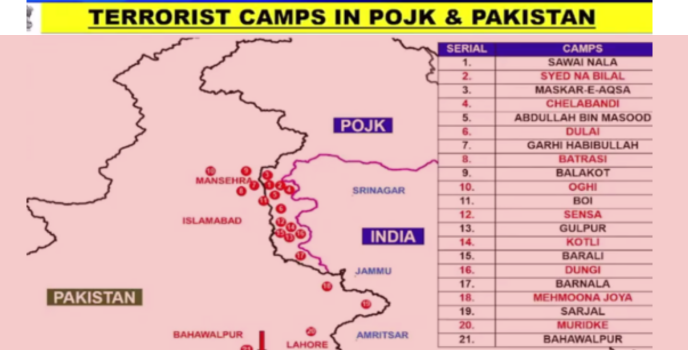

Nowhere is this tension more evident than in CPEC, the crown jewel of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). CPEC does not just run through Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK), which India remains vehemently opposed to, but also the volatile regions of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkwa and Punjab (where India’s Operation Sindoor attacked four terrorist camps). Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have repeatedly witnessed military attacks by balochi rebels on Chinese personnel and infrastructure. With Operation Sindoor signaling India’s readiness to escalate costs for proxy-based terror, any future conflagration in these zones would directly threaten Chinese investments and is strategically self-defeating.

Further, cross-border proliferation of jihadist ideology has implications directly for Xinjiang’s internal stability. Should militant flows from Pakistan and Afghanistan gain ideological traction among Uyghur populations or provoke international scrutiny of China’s selective counterterrorism approach, Beijing risks both domestic and reputational blowback. Meanwhile, China’s credibility as a leader of the Global South gets called into question if while presenting itself as a principled alternative to the West and India, its handling of Pakistan suggests otherwise. Africa, West Asia, and South/Southeast Asia as regions grappling with terrorism and insurgency could begin to see China’s selective moralism as situational rather than structural. The inconsistency dilutes Beijing’s claim to global moral leadership. Critically, Beijing’s reluctance to restrain Islamabad will inadvertently accelerate New Delhi’s strategic alignment with Western-led coalitions such as the Quad and deepen India’s engagement with partners like the United States of America, France, Israel, Russia and even the Gulf states. The more Beijing is seen as enabling South Asia’s destabilizer, the greater the incentive for New Delhi to counterbalance through external partnerships—a trend already evident in India's burgeoning defense and tech ties with Washington, Seoul, Canberra, Brussels, London and Tokyo among others.

In this regard, China must rethink the utility of its “iron-clad” partnership. It is no longer sufficient to view Pakistan as a counterweight to India or a loyal Belt and Road client. The relationship demands conditionality. It must apply calibrated pressure on Islamabad to reign in its terror networks and recognize it is not a choice between loyalty and condemnation but between strategic patronage and regional entropy. Unchecked proxies not only threaten India’s security—but also endanger the very infrastructure, influence, and legitimacy China hopes to sustain across the region.

Author

Eerishika Pankaj

Eerishika Pankaj is the Director of New Delhi based think-tank, the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA), which focuses on decoding domestic Chinese politics and its impact on Beijing’s foreign policymaking. She is also an Editorial and Research Assistant to the Series Editor for Routledge Series on Think Asia; a Young Leader in the 2020 cohort of the Pacific Forum’s Young Leaders Program; a Commissioning Editor with E-International Relations for their Political Economy section; a Member of the Indo-Pacific Circle and a Council Member of the WICCI’s India-EU Business Council. Primarily a China and East Asia scholar, her research focuses on Chinese elite/party politics, the India-China border, water and power politics in the Himalayas, Tibet, the Indo-Pacific and India’s bilateral ties with Europe and Asia. In 2023, she was selected as an Emerging Quad Think Tank Leader, an initiative of the U.S. State Department’s Leaders Lead on Demand program. She co-edited the ORCAxISDP Special Issue "The Dalai Lama's Succession: Strategic Realities of the Tibet Question" and edited the ORCAxWICCI Special Issue "Building the Future of EU-India Strategic Partnership: Between Trade, Technology, Security and China." She can be reached on [email protected]

Omkar Bhole

Omkar Bhole is a Senior Research Associate at the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). He has studied Chinese language up to HSK4 and completed Masters in China Studies from Somaiya University, Mumbai. He has previously worked as a Chinese language instructor in Mumbai and Pune. His research interests are India’s neighbourhood policy, China’s foreign policy in South Asia, economic transformation and current dynamics of Chinese economy and its domestic politics. He was previously associated with the Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS) and What China Reads. He has also presented papers at several conferences on China. Omkar is currently working on understanding China’s Digital Yuan initiative and its implications for the South Asian region including India. He can be reached at [email protected] and @bhole_omkar on Twitter.