The documentary specifically chronicles the aggrieved lives of different children in Yingzhou district: Gao Jun of Wang Dian village — a toddler afflicted with the disease who is being taken care of by his uncle; the three Huang children in Miao Zhuang village who have been recently orphaned; and Nan Nan, a young girl from Guo Zhuang village who is cared for by an American woman and the Fu’Ai charity. Over the course of the documentary, light is shed on the socio-economic conditions of the orphans and the discrimination that they face due to the general lack of awareness and misinformation regarding the disease.

Both Gao Jun and Nan Nan are infected children, who are ostracised by their village and had to lead isolated lives. This leaves the children vulnerable and traumatised; negatively affecting their mental health and making it difficult for them to socialise with their peers. Similarly, despite the Huang children being unaffected, they face severe discrimination due to the local community’s ignorance of how the virus is transmitted.

The lack of knowledge on AIDS not only resulted in the children being seen as disease-ridden but also cut them off from their families as everyone sought to distance themselves from members who had been associated with HIV-positive patients. For instance, Gao Jun’s uncle talks about how he struggles to take care of him, while simultaneously making sure that his own family remains unaffected by the shame attached to the disease. Nan Nan’s older sister also chooses to keep her disease a secret from her future husband out of fear that it would negatively impact her marriage. These perceived and personal stigmas attached to AIDS orphans in China are at the crux of the documentary.

In this documentary, the lack of social security and poverty in rural China is also underscored, which is in sharp contrast to the wealth one sees in urban centres. Poverty led parents to sell plasma for 53-yuan RMB and egg cakes; donating blood and earning money for it became such a craze that it even led to the creation of jingles like “Extend your arm, bear the pain of the needle. Then flex your arm, 50 yuan is earned.”

Furthermore, the lack of healthcare and understanding of medical needs makes it even more difficult for people with AIDS to seek help. Despite local officials from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasising AIDS sensitisation campaigns in the affected provinces as well as efforts undertaken by organisations like the Fu’Ai charity, it is apparent that they have made slow progress in getting rid of biases in people’s mentalities.

Infectious Diseases in China - A Case of AIDS/HIV and COVID-19

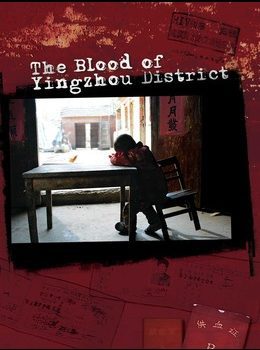

The impact and importance of the documentary —and the topic— became evident when Peng Liyuan, wife of China’s present president Xi Jinping, featured in a 2006 follow-up to the documentary as the ambassador of China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission. The short documentary titled Peng Liyuan and the Fu’Ai Charity showcased Peng’s visit to the Fuyang AIDS Orphan Salvation Association in the Anhui province. Since then, Peng Liyuan has spoken of Gao Jun as her friend while speaking at different forums as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Goodwill Ambassador for Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Additionally, Yang went on to release a documentary titled The Blood of Yingzhou District Revisited, depicting the lives of the same children highlighting how although much improvement has been made in their lives due to the growing understanding of AIDS in China, there is still much work left to be done.

China’s HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1990s spread rapidly along its southwestern regions where most of the cases were reported. One of the primary sources of the spread of the disease, as depicted in the film, was due to paid plasma donation programs in regions such as Henan and its surrounding provinces. The plasma donation camps were known to pool contaminated blood cells and inject them back into the donor for quicker recovery, enabling donors to sell more frequently. The blood plasma industry boomed significantly in the 1990s due to the economic incentives it provided in rural underdeveloped regions like Anhui, Guizhou, Hebei, Hubei, and Shandong amongst other regions. Moreover, social factors including economic incentives for plasma donations as well as inadequate health sanitation mechanisms also contributed to the outbreak of the disease. The disease was predominantly found among farmers in underdeveloped southwest and northwest regions as well as inland agricultural provinces resulting in the deaths of thousands. Moreover, when cases related to AIDS/HIV came to light, state suppression began taking prominence with various activists either imprisoned or exiled due to reporting on the outbreak. The government’s reluctance in admitting that the plasma economy was a significant cause for the spread of the infectious disease led to more than 75,000 children becoming orphans during the fatal years of the epidemic.

A similar strategy was enforced by Chinese authorities during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic when large-scale under-reporting of active cases as well as the lack of acceptance of the outbreak prevented adequate health measures to take effect. Furthermore, similarities between both AIDS and COVID-19 orphans could also be traced in the psychological effects infectious diseases have on children with several battling post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression symptoms.

Several parallels in the marginality, neglect and discrimination towards AIDS patients in China are particularly interesting to note, when viewed with the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies comparing the stigmatised attitudes towards the two viruses find that although people distance themselves from those diagnosed with either virus, such sentiments had a slightly lower proportion when it came to AIDS than COVID-19 (this could also be due to their differing transmission modes). Those who tested positive for COVID-19 witnessed multifaceted discrimination — several lost their jobs despite recovering from the virus; front-line healthcare workers and people associated with recovered patients were also stigmatised and COVID-19 patients were referred to as “little sheep people” on social media.

Comparatively, it was easier for AIDS patients than those infected with COVID-19 to be discreet regarding their affliction, given the moral judgement embodied in the disease. However, COVID-19-related stigma when compared to that of AIDS generated much more public panic given its media coverage. This was a result of the strict implementation of the nationwide public health policy, known as Zero-COVID, in order to curb community transmission of the virus. Under this policy, people are severely monitored by the government through technologies such as mass testing, health code scanners, drone surveillance, and mobile tracking. Hence, unlike with the AIDS epidemic, citizens are unable to keep their infection a secret or manage complete isolation without depending on others or the state for daily deliveries.

China’s hard-line Zero-COVID approach saw a recent wave of protests by citizens, which factored into the dilution of the stringent policy. However, with the relaxation of restrictions, China is currently witnessing an upsurge in COVID-19 infections triggering global concerns regarding a subsequent fatal outbreak. The increase in the number of cases has also brought to light the inefficacy of Chinese vaccines as compared to the mRNA ones manufactured by western companies. The recent outbreak has also concretised global concerns regarding China’s vaccines and its inability to prove as a vital deterrent against the virus, which has also been reflected in the hesitancy of many countries in inoculating their population with Chinese vaccines. Unlike the rest of the world, China prioritised the vaccination of its working-age population over the elderly. With the current surge in COVID-19 infections, the low inoculation rate amongst its elderly population has raised the risk of fatalities as well as the spread of infections amongst China’s vulnerable population.

There is a lot to take away from the short documentary, especially given the parallels one can draw from the similarities in the aftermath of an outbreak of infectious diseases, decades apart. In conclusion, The Blood of Yingzhou District, demands attention towards the suffering that fatal diseases often lead to, more so when the consequences are faced by young children. China’s AIDS epidemic may have been overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet much of the situation remains similar to how the epidemic was dealt with — drenched in social stigma and feeble state accountability.

Author

Ahana Roy

Ahana Roy was previously a Research Associate and Chief Operations Officer at Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). She is a postgraduate in Political Science with International Relations from Jadavpur University. Her areas of interest include non-traditional security studies with a focus on gender and sexuality studies, society, and culture in China specifically and East Asia broadly. She can be reached on Twitter @ahanaworks and her email [email protected]

Ratish Mehta

Ratish Mehta is a Research Associate at the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). He is a postgraduate in Global Studies from Ambedkar University, Delhi and works on gauging India’s regional and global political interests. His area of focus include understanding the value of narratives, rhetoric and ideology in State and non-State interactions, deconstructing political narratives in Global Affairs as well as focusing on India’s Foreign Policy interests in the Global South and South Asia. He was previously associated with The Pranab Mukherjee Foundation and has worked on projects such as Indo-Sino Relations, History of the Constituent Assembly of India and the Evolution of Democratic Institutions in India. His forthcoming projects at ORCA include a co-edited Special Issue on India’s Soft Power Diplomacy in South Asia, Tracing India’s Path as the Voice of the Global South and Deconstructing Beijing’s ‘Global’ Narratives.