Introduction

Women in China do not hold up “half the sky” yet. Since the reform and opening up policy was initiated in China, female participation in the labour force and other avenues of economic life has increased considerably. However, promises made by top Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders about promoting equality between the sexes are yet to manifest into greater participation by women in China’s political system. Female representation in Party leadership organs has been limited to the Central Committee and has stagnated since 1978. In light of the upcoming 20th National Party Congress (NPC), the status of female participation in Chinese politics raises several questions: Who are the women expected to take up top leadership positions at the Party Congress? Can we expect an increase in female representation in the CCP’s leadership? How have female leaders participated in elite politics and what conditions drive their participation?

Incomplete Role of ‘Affirmative Action’ in Progressing Gender Equality

Chinese women’s participation in politics has arguably, though still not enough, progressed over the years, mainly due to the promotion of affirmative action policies China adopted in the 1990s which essentially served as a catalyst in enabling women to design, implement and pursue policies which are incorporated with a gender perspective. Gender equality has been touted as a fundamental policy of the Party-state since the establishment of the PRC, with both the 1982 State and Party Constitutions promoting affirmative action.

In this context, the CCP enacted various affirmative action policies and laws to emphasise women’s political participation and increase their representation in different political bodies. For instance, in 1992, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests was passed (later amended in 2005). In 2008, the NPCC formally introduced a gender quota of 22%. Under the guidance of the State Council, the Women Work Committee organised 15 groups to assess the implementation of the gender policy. Furthermore, bodies like the Central Organisation Department (COD) and the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF) also initiated several policies on women’s participation in Chinese politics.

Nonetheless, while affirmative action policies have positively impacted women’s political participation, these policies are met by resistance and have been given lesser priority than policies which focus on economic growth. Moreover, the affirmative action policies have remained hollow as they only cover the “four leading bodies” (si tao ban zi) — the Communist Party Committee, the People’s Government, the People’s Congress (NPCC) and the People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) — and have not been able to ensure that the government meets its targets regarding boosting women’s participation in leading state and Party positions.

The Lack of Gender Balance in Chinese Leadership

Female participation within China’s political elite has stagnated as men continue to wield political power. Despite constituting roughly 48.7 per cent of the population, women hold less than 8 % of the seats in the 19th Central Committee (CC). Among the current 376 members of the 19th CC, only 30 (7.9 %) members are female; 10 full members and 20 alternate members. Furthermore, only one woman —Vice Premier Sun Chunlan —is currently part of the 25-member Politburo . No woman has ever been part of either the Politburo Standing Committee or the Central Military Commission (CMC). Out of 31 provincial Party Secretaries, only one is a woman, Shen Yiqin, and among provincial-level governors, only two are women —Wang Lixia and Xian Hui.

Not only does the data suggest a dearth of women in positions of power, it also sheds light on how prospects for women’s participation and upward mobility in elite politics of the CCP are limited. Women are relegated to less important positions the higher their ranks become, such as education, United Front (propaganda) work and social policies; top positions with real power remain seemingly reserved for men. There is a clear bias towards men, despite proclamations of equal opportunity by the Party, especially in regard to top leadership roles. For instance, although women are better represented in the Party establishment at the National People’s Congress (NPCC) (25%) or the grassroots level, their representation in leadership bodies like the State Council is abysmal. Only one member of the Executive Committee of the State Council is a woman, while all of the 26 ministers of the State Council are men.

Women’s Status in China: Are They Unseen?

These institutional barriers are further complicated by the ingrained cultural and traditional gender norms in China which suggests that “those in power just don’t want women to get higher political leadership because that would threaten the status quo and the patriarchy.” Quotas maintained for women in provincial, municipal and county-level leadership positions are rarely met. Although the gender quotas kept aside for women’s inclusion in these levels of government are often vaguely stated, the combination of the gender quota, the ethnic minorities quota and the non-CCP quotas makes women leaders more likely to be non-Han and non-CCP members than men. Moreover, the dominance of men in political positions has consequences for decision-making and policymaking. Interestingly, data suggests that female legislators who hold about 20% of seats in the National People’s Congress (NPCC) sponsor 44% of all bills passed in the 12th NPCC. This demonstrates that women are both underrepresented even as they outperform men in policy formulation.

Women’s political participation also represents the status of women in Chinese society. The topic of women’s rights in China, in recent times, has become especially sensitive. Multiple incidents of gender-based violence, discrimination and sexual harassment have been quickly stifled online before such cases gather momentum. Government censorship has used social media platforms like Weibo to control the narrative and shift focus to other matters. After a video of a gang of men ruthlessly beating up several women became viral on Weibo, the platform muted, suspended and banned numerous accounts that it claimed were “inciting conflict between the genders.” In November 2021, Peng Shuai alleged that she was being sexually harassed by former Chinese vice-premier, Zhang Gaoli, on Weibo; the post was soon deleted and she virtually “disappeared”, while no action was taken against Zhang, a retired top CCP politician. Outside China, in recent times, fake pro-CCP Twitter accounts have targeted and attacked women of Asian origin with public platforms, especially journalists working at Western media outlets and human rights activists.

The lack of female representation in the upper echelons of Party leadership has resulted in the creation and implementation of policies with a strong bias toward men. In an effort to reverse declining birth rates, China recently removed the two-child restriction and has encouraged couples to have a third child, releasing guidelines to support the implementation of such policies. Furthermore, the Party called on women to accept their “women-specific physical and mental characteristics, reproductive and breastfeeding functions” (妇女特有的身心特点、生育和哺乳功能). Chinese President Xi Jinping himself has emphasised traditional Confucian family values and stressed on women to be good wives and mothers as foundational to the advancement of Chinese society. Although the Party claims women play an instrumental role in the rejuvenation of China, they have a limited say in the creation of policies directly affecting women and their participation in this rejuvenation effort.

Changing Criterion for Women’s Participation in Politics

More recently, the criteria for participation in leadership roles have drastically changed from those who entered politics purely based on personal connections to participation based on competence and leadership abilities. The era of the Cultural Revolution witnessed three women holding seats on the Politburo, namely the wives of Mao, Zhou Enlai and Lin Biao —Jiang Qing, Deng Yingchao and Ye Qun, respectively. This coincides with the 10th and 11th Party Congress held in 1973 and 1977, the only times when women’s representation in the Central Committee (CC) was more than 10%.

Now, women from science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) backgrounds make up most of the female Party candidates in the CC. Women like Cao Shumin, newly appointed Deputy Director of China’s Cyberspace Administration and an alternate CC member, are a prime example of the kind of women rallying to be part of China’s top leadership. Prior to her promotion as Deputy Director, she was President of China Academy of Information and Communications Technology and Vice President of Telecommunications Research Institute. It is quite probable that exemplary women like Cao will attain full membership status in the CC in the 20th NPC. It remains to be seen to what extent the Party follows up on its stated intention to promote more female candidates and ethnic minorities.

Women in the 20th Party Congress: Who Can We Expect?

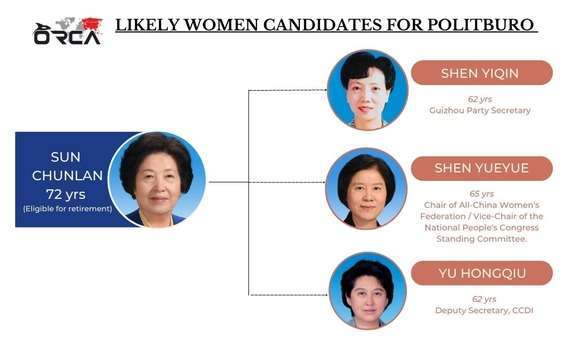

According to the list of delegates for the 20th NPC, women’s representation is around 33% — 9% more than the 19th NPC which saw a 25% participation by women. This suggest that there is some hope for the upcoming Part Congress of the CCP. Sun Chunlan, the Vice-Premier of China, who currently serves on the Politburo is expected to retire at this year’s Party Congress as she is past the retirement age. Beginning in 2020, Sun has been on the frontlines of pandemic relief efforts in China. Ideally, based on experience and performance, Sun should be one of, if not the “number one person in the party”, however, as per the political system, “she’s not qualified”. Although it is much more likely that she will be replaced by another woman, the pool of female candidates is already small to begin with. According to Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA), there are only two women eligible for a seat in the Politburo — Shen Yiqin, Party Secretary of Guizhou and Shen Yueyue, Chair of All-China Women’s Federation.

Shen Yiqin is an ethnic Bai minority and a full CC member who has worked extensively in the province of Guizhou. She has served as the provincial Party Secretary in various senior roles and in the military apparatus as well. Over the course of her career, she has worked under top CCP heavy hitters such as Hu Jintao, Li Zhanshu, Zhao Kezhi and Chen Min’er, making her a top contender for a position in the Politburo. Apart from Chen, the rest of the 9 full CC members are either past the retirement age or have been given nominal roles to fulfil. Shen Yueyue is the other candidate most likely to replace Sun Chunlan. However, although she is higher-ranked and is young enough to be considered to be in the Politburo, she has not yet been promoted from her current position since 2013. Nonetheless, Shen has worked closely with Xi Jinping and was part of his entourage to Hong Kong in June 2022 to mark the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to mainland China. This suggests that women have to work with important male political leaders to be considered suitable for positions of power.

Conclusion

It is not clear whether the 20th Party Congress is where Beijing will be able to shatter the persisting ‘glass ceiling’ women in Chinese politics have to face. Although female representation has increased in general, female representation in the Politburo is not likely to increase anytime soon and women politicians holding office in the Politburo Standing Committee seems like a distant dream. What is clear however is that, if the institutional, societal, cultural and perceived biases against women holding real power are not addressed by the CCP leadership this coming October, it will only be detrimental to the holistic development of China’s political system in the years to come. In light of the upcoming 20th Party Congress, the CCP will have to deal with public pressure and social unrest revolving around women’s issues in Chinese society. The Party can only erase so much of a woman’s lived experience; it must find ways other than censorship to address the issue of women’s status in China.

Author

Ahana Roy

Ahana Roy was previously a Research Associate and Chief Operations Officer at Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). She is a postgraduate in Political Science with International Relations from Jadavpur University. Her areas of interest include non-traditional security studies with a focus on gender and sexuality studies, society, and culture in China specifically and East Asia broadly. She can be reached on Twitter @ahanaworks and her email [email protected]