Broad and shallow approach to Asian countries persists in Polish society to this day. India is no exception – Polish people often talk about Indian food, Bollywood movies, but there is no knowledge about the huge economic and geopolitical potential that lies dormant in this country. The knowledge from the expert bubble is slowly seeping into the rest of the society – the knowledge that this country is located in a place that is increasingly called the new geopolitical center of the world – Asia. China is currently breaking through into Poland’s mainstream discussion about international relations, but India is still a country not well studied. It is in the interest of the Polish government to build a conscious foreign policy in this region of the world. Can India become an important Polish partner in Asia? From the point of view of a young researcher from Poland, whose main field of interest is China, it is difficult to answer this question unequivocally. To answer the aforementioned question, it is worth examining the current state of Poland-India relationship, its placement in the European framework, as well as the possibilities and difficulties lying in them.

India has more than 1.3 billion inhabitants and is the seventh largest economy in the world, growing the fastest among G20 members. With growth rates of more than 7% of GDP, by 2030 it will not only be the most populous country, but also the third biggest economy in the world. As the world’s largest democracy, India has long advocated for a rules-based, free, open and equal world order, offering its leadership on international platforms at times of crises while following a policy of strategic autonomy. This country has enormous potential at present, and in the future, it can become the third pole of economic and geopolitical power, just behind the US and the People’s Republic of China. From the Polish perspective, it is necessary to embed this knowledge in both academic and political contexts so as to a nexus with active policymaking.

When it comes to political relations, one can certainly talk about a friendly atmosphere between Poland and India, which can be a prelude to strengthening contacts between states. Apart from Pakistan, India is the only South Asian country with a Polish embassy with the Ambassador of the Republic of Poland in New Delhi is also accredited in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka. New Delhi is also one of the few Asian capitals where Poland not only has a diplomatic mission with military attachés, but also maintains the Institute of Polish promoting the country’s culture. In 2018, the Polish Investment and Trade Agency opened a new Foreign Trade Office in Mumbai. In 2019, the first visit of an Indian Foreign Minister to Poland in 32 years took place when Dr. S Jaishankar visited. It underlined the positive accents of cooperation between India and Poland in the international environment. In a joint statement, it was announced that the Polish side appreciated India’s support for the candidacy of Poland for a non-permanent seat in the UN Security Council for years 2018-2019 and expressed support for India’s candidacy for a non-permanent seat for years 2021-22. It is worth noting, however, that despite the mutual support, this visit is one of the few that representatives of both governments have made to each other.

The lack of regular contacts has its reflection in economic data. Although Poland is India’s largest trading partner in the Central European region, according to Indian statistics, the total trade turnover in 2019 amounted to only USD 2.85 billion. India’s exports to Poland accounted for 0.48% of India’s total exports. Only 0.15% of India’s imports in 2019 were covered by Poland. It is worth noting that these are data from before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, trade turnover between Poland and India decreased by 4.2%, which amounted to USD 2.73 billion. The pandemic situation has had a negative impact on contacts between countries, further reducing the dynamics of business contacts.

At present, regrettably, foreign policy towards Asian countries is not the strongest point of the Polish state. Despite the existence of analytical centers and experts with the knowledge needed to create a strategy to face the challenges and opportunities associated with the gradual growth of Asian countries, there is a lack of political will to implement comprehensive solutions. This is particularly evident in the case of China. In 2015, the Law and Justice party came to power, and approached Chinese proposals made under the aegis of the New Silk Road quite enthusiastically. In the same year President Andrzej Duda participated (although it was a format intended for prime ministers, not heads of state) in 16+1 format summit in Suzhou, after which the Chinese organized his official visit; less than a year later, President Xi Jinping visited Warsaw. Until now, around 40 bilateral agreements have been signed. However, as Professor Bogdan Góralczyk from the University of Warsaw notes, the development of these contacts was significantly weakened after Donald Trump came to power and declared a trade war with China in 2018 – Poland is strongly associated with Washington in terms of security and strategy. For this reason, the main topic discussed in Poland in the context of China is primarily the issue of suspicions against Huawei and the debate on 5G technology.

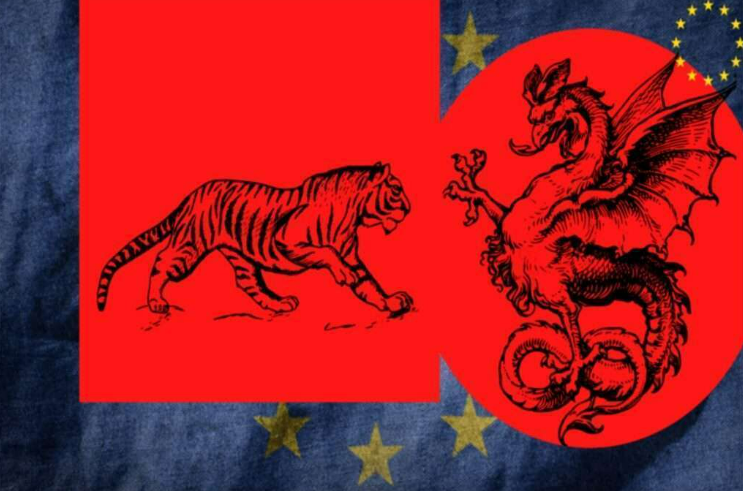

The Chinese issue is a very important component of the context of Poland-India relations, as it concerns what foreign policy options not only Poland, but also the European Union has. This is particularly important due to the fact that Poland – firmly embedded in the economic and political system of the EU – is not capable of pursuing a policy completely detached from the interests of the European community. So, can India compete with China for Poland and Europe?

Both Poland and India support the law-based international order and the free trade system. This naturally facilitates bilateral cooperation as well as that within the European Union (which has now adopted a joint European-Indian roadmap to year 2025). This is particularly important when one looks at difficult relations of the EU with the People’s Republic of China, in which the lack of European unity on many issues makes it difficult to create common areas for cooperation. The lack of a systemic response particularly highlights the dichotomous approach to Beijing as both a partner and a “systemic rival.”

Economically, the European Union now wants to reduce its dependence on Chinese and other foreign suppliers and limit the ability of companies supported by foreign subsidies to buy EU companies or participate in public tenders. India, in turn, is focusing on increasing access to various fields of its economy, liberalizing regulations, facilitating operations on the market and creating new business opportunities for foreign partners. At the same time, the current trade exchange between Poland and India does not reflect the potential of these relations. All these facts provide Poland with a window of economic opportunities.

Geopolitical challenges and the question of different values (as in the case of China) do not seem to be a critical issue in the case of relations with India, which makes it possible to present them as a less controversial choice when it comes to the development of economic and political relations. The current situation will not make India a substitute for cooperation with China, but it may open the door to greater involvement in the development of relations. Positive incentives for the development of relations also come from the United States. The reason is the increasingly closer partnership between the US and India and the tightening of NATO’s position on China.

However, this does not mean that the path to cooperation is one without obstacles. The Polish and European elites lack an understanding of India as a major player not only in the rivalry between the US and China (to which the European Union is forced to respond if it wants to remain a major player in the international community), but also on the global stage. The lack of understanding is mutual: both India and the European Union have complex political systems, and in the case of both actors, the expert community that could explain and interpret such complexity is small.

There is another potential problem between Europe and India. This is a matter of concern about India’s position as a so-called “swing state”. Researchers Richard Fontaine and Daniel Kliman have defined swing states as countries that have large, developing economies and occupy central positions in a given region. They are increasingly active at the regional and global levels and want changes in the existing international order, but they do not seek to break the overlapping network of global institutions, rules and relationships. Despite significant changes in foreign policy made from year 2014, India continues to be guided by the idea of “strategic autonomy” – an independent foreign policy aimed at maximizing the realization of national interests. For this reason, it is worth remembering that common values can help in cooperation, but it is common interests that create a real partnership.

In the final analysis, Poland has room for maneuver when it comes to the development of economic relations with India, but the matter is a bit more complicated when it comes to political relations. Nowadays, Poland – unlike India – cannot afford strategic autonomy. This forces it to define its foreign policy within frameworks such as the European Union and NATO. The situation is also complicated by the Chinese issue. It can be expected that due to the cooling relations between the EU and the PRC (best examples are the frozen Comprehensive Agreement on Investment or the Lithuanian situation), the European community will look for alternative partners in Asia. Taking into account the rather passive Polish policy towards China, it is not an exaggeration to say that the matter looks similar in relation to India. It is therefore primarily at the European level that decisions will be made as to whether there will be a positive development between the EU and India. There are many potential benefits to making this decision, but it is also not without its difficulties. Time will tell what the leaders of the European community will decide to do.

Author

Patryk Szczotka

Patryk Szczotka (@p_szczotka) is a MSc student at “China and International Relations” double degree program at Aalborg University and the University of International Relations (国际关系学院) in Beijing. His research interests include political and economic relations between the CEE countries and the PRC.