China, over the past decade, has forged closer ties with the Western Balkan (WBs) states through the expansion of the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) and the 16+1 Initiative (earlier the 17+1 Initiative). In what was earlier seen as the backyard of Europe and the US, the Western Balkan region has steadily become a theatre of Chinese geopolitical and geo-economic influence via the BRI. The recent Euro Tour of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to Serbia, Greece, Albania, and Italy is a further testament to the importance that Beijing attaches to the strategic value of the region. As China looks to pitch the Serbia Model – large funding under BRI projects across critical sectors with lesser scrutiny- to Europe, what factors are shaping its outlook, and what is the desired outcome?

While Beijing vies for influence in the WBs, it has also been looking at ways to contain the downward spiral in its relations with the European Union (EU). This downward spiral can be attributed to the EU’s angst over China’s human rights record vis-à-vis Uyghurs, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Tibet. Moreover, China is also worried about the European parliament’s recent vote to support stronger relations with Taiwan.

Concurrently, recent developments like the EU’s adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy and the announcement of the Global Gateway are also being closely watched by Beijing. As a result, China’s play in the WBs seems to be aimed towards presenting the Serbia-model to Europe to lure the latter to Beijing’s BRI fold and expand its overall sphere of influence, and offset growing EU-Taiwan ties. However, maneuvering its many divergences with Europe will remain a key challenge for the Chinese government.

China & the Western Balkans: Looking at the Bigger Picture

WBs has traditionally been Europe and US’ bastion, with both having provided heavy investments to the region in terms of economic and military assistance after the breakup of erstwhile Yugoslavia. Since it provides access to the “inner core of Europe” through the Mediterranean, the WBs have been a point of geostrategic competition for decades.

The increased attention towards China and Asia has led to a neglection of the WBs by the Transatlantic allies. China has grabbed this opportunity and infused huge investments in the WBs’ nations. It has also increased the investment intensity steadily. In doing so, China is reviving its communist links to Albania (in the 1950s) and the former Yugoslavia (1970s) to forge stronger relations in the region.

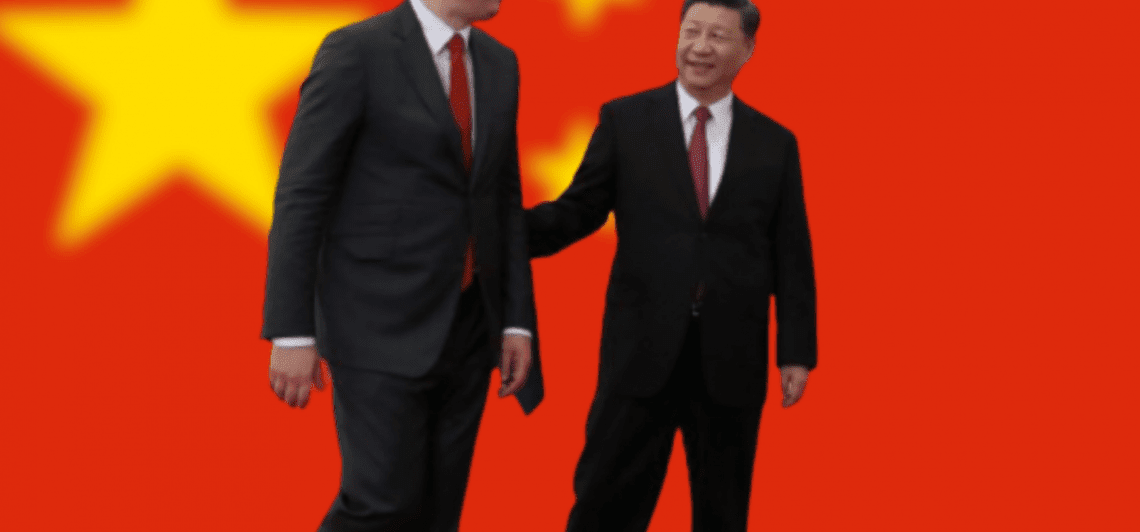

To understand China in the WBs, it is important to identify Xi Jinping’s BRI as the key element in Beijing’s outreach to the region and Xi Jinping’s foreign policy focused on the “Chinese Dream”. The WBs region, currently in need of infrastructural financing, has been identified by China as a possible region for the expansion of BRI.

Here, the 16+1 Initiative, which aims to promote trade and investment between Beijing and the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries while also looking to expand China’s diplomatic heft, takes on critical weightage.

As of 2020, China has invested the most in the energy and transportation sectors- constituting 64/102 Chinese activities in the region. In the second phase, it has planned for investments to build digital infrastructure in the region in the form of information and communications technology (ICT) projects. The idea behind these projects is to provide China access to the European market and strategic access to various transit points that connect China to Europe. Here, the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Route (LSER) is the key region-wide initiative undertaken under the BRI, and Chinese companies have picked up major stakes in various ports of Greece, mainly the port of Piraeus.

Thus, China has successfully leveraged the gaps left by Europe and US’ engagements in the WBs through strategic investments. Certain advantages have helped China to establish its presence in the region. For instance, a major concern for WBs is the European expectation to implement governance reforms in return for support- something which many WBs’ nations have been reluctant to carry out. Furthermore, as Chinese investments arrive with lesser scrutiny as compared to EU-led aid, it attracts the WBs nations to indulge in business with Beijing. Hence, it would not be an exaggeration to state that Chinese investments in the WBs are part of Xi Jinping’s larger strategy aimed at laying out the advantages of the BRI and presenting the Chinese economic model as superior to the Western economic model.

Countering Taiwan: Selling the Serbia Model

China and the EU have been witnessing a downward spiral in their relations. Even though China remains the EU’s largest trading partner, both have failed to reach a middle ground in ramping up their economic ties despite the intention to do so. The ratification of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) has also been frozen since May 2021 after China imposed sanctions on several EU individuals and entities. The EU had reacted with countersanctions on the Chinese while France, the UK, and Germany sent military vessels into the South China Sea this year- inviting strong reactions from Beijing.

Nonetheless, China recognizes the importance Europe holds. In a video meeting with Angela Merkel recently, Xi Jinping stated that both sides “believe that the common interests of China and the EU far outweigh contradictions and differences”.

To accomplish this goal, Serbia has become a tool for China to tell a success story to the EU. Serbia is now a hub of Chinese investment in the WBs- with more than 50% Chinese funding reaching it out of all the other WBs nations. The Budapest-Belgrade railway stands as the flagship BRI project in Europe, being accelerated after Wang Yi visited Serbia.

Beyond an economic partnership, Serbia provides Beijing with an ally in Europe that would support its core concerns. This is exemplified in Serbia’s steadfast support for the Chinese position on Taiwan and Beijing’s non-recognition of Kosovo as an independent state.

While mainly driven by economic factors, China’s involvement with the WBs has certain strategic and geopolitical connotations. This can be understood in the backdrop of China positing Serbia as BRI’s success story in the WBs and using the same to accomplish two goals- luring the EU to its BRI fold and building diplomatic support against Taiwan.

Identifying Cracks in the Chinese Approach: A Chance for Strengthening the Transatlantic Alliance?

China making inroads into the WBs may appear to be lucrative, but it is not free from cracks. These cracks can be classified under two heads- lack of a system of checks and balances in the BRI projects, and threats that might emerge similarly to other BRI projects across the globe.

Talking about the system of checks and balances, China is currently offering BRI projects to the WBs nations through the Chinese EXIM Bank and the Chinese Development Bank (CDB) loans. These routes offer lesser scrutiny in comparison to European or American investments. While this lure is enough to pull the WBs nations- lax governance, corruption, and bribery are just a few of the issues that are already coming up.

Such dilemmas are further accentuated by threats that emanate from such BRI projects. It has been widely documented in Africa, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka that loans provided for infrastructure projects under the BRI have often led to debt traps for these countries. As a result, China ends up controlling the critical assets of these countries as payback. An example of this was Beijing taking control over the strategic Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka.

In the case of WBs, it would not be far-fetched to be fearful of such debt-traps emerging, since the WBs nations are also developing nations and provide room for China to take control of critical assets for its national interests, especially transit points, and maritime routes. Similarly, it also raises concerns of potential dual-use ports coming up in the region at the behest of China, in a similar fashion to the South China Sea.

Apart from the strategic fears, it has been observed in countries like Sri Lanka that along with Chinese investment, Beijing has subtly been spreading its cultural influence, often at the cost of local traditions and culture (exemplified in Mandarin sign boards replacing Tamil language signboards). In the case of WBs, it becomes important to anticipate such occurrences well in advance as China increases its footprint in the region.

The human rights discourse is extremely crucial to scrutinize as well. It has already been reported that Chinese construction sites are using slave labour in Serbia; while a Chinese steel mill has been flouting environmental guidelines- increasing the risk of cancer in nearby areas. These instances are not very different from China’s dismal human rights record in foreign countries. Similar instances have taken place in Pakistan, Africa, and elsewhere. This would invoke some fears in WBs.

These cracks highlight the downside of China’s relations with the WBs nations and call for exercising caution by the WBs, while offering a chance to the Transatlantic alliance to reassess the terms on which it wants to negotiate with China in the future, especially the EU. Since China wants to reengage with the EU on the economic front, the clear divergences between the two over ideology and human rights cannot be ignored.

China has not shown any inclination to find a middle ground on these two issues. On the economic front too, the recent announcement by the EU to launch the Global Gateway initiative, a €300 billion plan for infrastructure development across the globe, is in direct competition with China’s BRI. As the EU adopts a more independent approach in foreign policy, with a pivot towards the Indo-Pacific and balancing China, how Beijing and Brussels navigate the vagaries of their relationship, remains to be seen. China has effectively managed to exploit the gaps in assistance left by the United States and the EU to the WBs. While it may cast doubt on the EU’s and US’ leadership in the WBs, it also offers them a chance to rebuild the Transatlantic Alliance —which has taken key hits post the signing of the AUKUS and hasty US-led withdrawal from Kabul resulting in the swift return of the Taliban —by using the WBs as a catalyst.

A major concern that should be focused on by both EU and the US should be the membership issues in the EU of the candidate countries from WBs who have long kept away due to certain expectations by both. With the EU and the US identifying China as the key future challenge, the WBs should serve as the driver behind a stronger Transatlantic alliance.

Author

Bhavdeep Modi

Bhavdeep Modi is former Senior Research Associate at ORCA and he is also a Visiting Researcher at Red Lantern Analytica (RLA), a New-Delhi based think-tank and has previously worked with Mr. Ninong Ering (former MP & currently MLA, Arunachal Pradesh). Mr Modi is also a former Teach for India Fellow and has worked as a political consultant in the past. He has interned at CLAWS, Chase India, and office of Mr. Anurag Singh Thakur (Minister of Sports, Youth Affairs and Minister for Information & Broadcasting). A lawyer by degree, he has also done an MA in Diplomacy, Law & Business with a specialization in Defense & National Security studies.