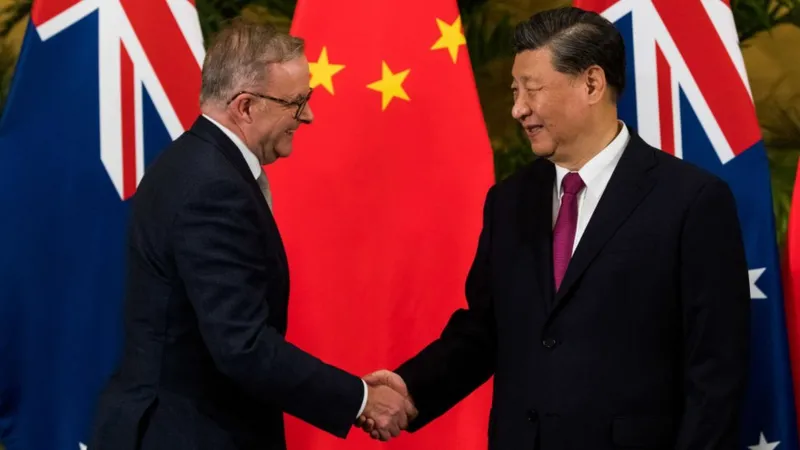

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s week-long visit to China has confirmed a reset in bilateral ties between Beijing and Canberra. Typically characterised by a considered balance of strategic competition and economic interdependence, Australia’s China policy has assumed pragmatic overtones under Albanese. The idea that “dialogue needs to be at the centre of our relationship” reflects an approach to stabilisation that signals greater stability. Beijing too has indicated its willingness to pursue stability, evidenced by the largely positive coverage of Albanese’s visit by Chinese state media, as well as President Xi Jinping’s declaration that Australia-China ties have “turned around”. Calling a truce to a nearly decade-long trade war and open diplomatic confrontation between China and Australia raises the question; who won, and what was lost?

The shift from open hostility to pragmatic engagement in China-Australia relations is a function of compromise and de-escalation. Built into these calculations are implications for the foundations of Australia’s China policy; economic dependency, emphasis on human rights, participation in US-led alliance architecture and competition for regional influence in the Pacific. For China, the Albanese visit may just have secured diplomatic wins, advanced its narratives on trade and projected its primacy as a strategic partner.

Advantage China?

The fundamental tenet of the Australia-China rapprochement is the importance of mutual respect and what Xi Jinping in his remarks to Albanese has called, “commitment to equal treatment”. The language of equal treatment and mutual respect, a prerequisite of Australia’s strategic equilibrium policy, aligns with Beijing’s long-held expectation of being treated as an equal, or equal to the US in importance, by Western/European allies of the US. Although the strategic equilibrium framework has given Australia greater manoeuvrability, it also accepts China’s elevated significance to Australia’s security and stability.

Moreover, the stability and predictability of a dialogue-driven approach suits Beijing’s interests, which are presently threatened by global economic uncertainty and volatility in its relationship with the US. Xi Jinping’s statement on upholding the overall direction in China-Australia relations, “no matter how the international landscape may evolve”, reveals that securing predictability was in Beijing’s interests, now more than before.

Trade, Security and Human Rights

The outcomes and optics of Albanese’s engagements with China concerning the core components of Australia’s China policy - trade, security and human rights - reflect an acceptance of Beijing’s position and reinforce China’s strengths. China’s economic primacy to Australia came to the forefront with both countries planning to review implementation of the China-Australia FTA (ChAFTA) and Albanese stating that China is Australia’s most important trade partner. The deepening of trade ties was cemented by agreements to expand trade in agricultural products like canola, lobbying for iron ore exports and greater customs cooperation, which further Australia’s economic dependence on China. In the case of iron ore, which accounts for 53% of Australia’s exports to China, Canberra was keen to secure contracts from Chinese steelmakers for green steel, playing to Beijing’s economic strengths that stem from economic interdependence with Australia.

In the security domain too, Beijing retained the advantage by declining to take a softer position. Albanese’s concerns about China’s live-fire military exercises off the Australian coastline in late February 2025 were brushed aside by Xi Jinping, who justified Beijing’s actions by stating, “China engaged in exercises just as Australia engages in exercises.” The absence of compromise or conciliation from Beijing on power projection in Australia’s neighbourhood means China’s attitude to Australia’s security concerns will remain unchanged and assertive.

The other tenant of Australia’s China policy is human rights- an area where China has remained firm in its stance. Although Albanese raised the issue of jailed Australian writer, Yang Hengjun, no “immediate outcome” is forthcoming. Beijing is keenly aware of the importance of securing the release of Yang Hengjun for Australia, and the domestic political win it would represent for Albanese. It will perhaps leverage this for concessions in future negotiations. Moreover, the reality that China does not share the same perspective on human rights as Australia was on display when Australian journalists accompanying Albanese on his visit were detained in Beijing, and released only after diplomatic intervention. Albanese’s response that ‘China has a different system with the media’ suggests Australia is conceding to Beijing’s position on civil liberties like press freedoms.

Overall, Beijing’s position on key issues was unchanged and in fact, saw Australia play to, or accept, China’s strengths in terms of economic leverage and power projection. Moreover, the optics of the Australia-China reset also reinforced Beijing’s broader, global objectives.

Australia: A Battleground for Perception

The dynamics of the China-Australia reset strengthen Beijing’s global narratives and interests in a variety of ways, constituting significant wins for China. First, by championing stability in bilateral relations, China projected itself as a stabilising force, a contrast to the US that China has attempted to draw in all its diplomatic engagements since the Trump presidency. Canberra too has highlighted that stability with China is crucial for security and prosperity, which reinforces China’s projection as the more reliable power in Asia Pacific.

Secondly, the perception of reliability that China has sought to cultivate is also reflected in how leaders of US and China engaged Australia; Albanese has not secured a meeting with President Trump yet, but secured a private lunch with Xi Jinping, a rare opening symbolising significant political and personal investment. By contrast, Trump’s early departure from the G-7 meeting led to the meeting between Albanese and Trump being cancelled, which has only heightened the contrast in China and the US’s approach to leadership-level visits with Australia.

Third, Australia’s decision to engage pragmatically with Beijing is a demonstration of strategic autonomy. A manifestation of strategic autonomy was Albanese’s interest in cooperation with Chinese science and technology businesses in the medical technology sector, a position that differs meaningfully from how the US has limited its technology cooperation with China. As a US alliance partner, faced with pressure to increase defence spending, growing economic uncertainty and intensifying geopolitical competition in the Indo-Pacific, Australia has perhaps set the tone for US allies like Japan and South Korea to engage more independently with China, outside the framework of their relationships with the US.

Implications and Road Ahead

Beijing has emerged from the China-Australia trade war and subsequent reset with its strategic advantages intact and gaining tacit acceptance of China’s long-standing positions on key issues, like power projection in Australia’s neighbourhood and human rights. The dynamics of the reset have also furthered the self-image that China has projected; a more reliable economic and strategic partner in Asia-Pacific. These outcomes have pressing implications for broader strategic realities like contestation in the Indo-Pacific, competition for influence in the Pacific Island states and defence partnerships like AUKUS.

For one, China’s insistence on conducting live-fire drills off the coast of Australia could mean that Canberra’s rapprochement opens the door for more frequent military power projection in Australia’s neighbourhood. A willingness to engage Beijing as an equal partner through a dialogue-centric approach perhaps also signals a normalisation and future intensification of Chinese influence in Pacific Island states, Australia’s immediate neighbourhood. Moreover, with the AUKUS review underway in the US, and facing pressure to increase defence spending, Canberra may find itself increasingly forced to engage with Beijing independently on security concerns, weaking the deterrence pillar of its strategic equilibrium policy. It could also dampen the intensity of Australia’s participation in multilateral frameworks like the QUAD, which implicitly focus on China. Australia will also have to think more pragmatically on how it navigates the Taiwan question; balancing the US’s insistence on choosing a side with its recognition of the One-China policy, as it did recently. The China-Australia reset has secured advantages for Beijing, and normalcy in a key relationship for Australia, but it also presents several China-centric challenges for Canberra to navigate in the road ahead.

Image Credit: Getty Images

Author

Rahul Karan Reddy

Rahul Karan Reddy is Senior Research Associate at Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). He works on domestic Chinese politics and trade, producing data-driven research in the form of reports, dashboards and digital media. He is the author of ‘Islands on the Rocks’, a monograph on the Senkaku/Diaoyu island dispute between China and Japan. He is the creator of the India-China Trade dashboard, the Chinese Provincial Development Indicators dashboard and co-lead for the project ‘Episodes of India-China Exchanges: Modern Bridges and Resonant Connections’. He is co-convenor of ORCA’s annual conference, the Global Conference on New Sinology (GCNS) and co-editor of ORCA’s daily newsletter, Conversations in Chinese Media (CiCM). He was previously a Research Analyst at the Chennai Center for China Studies (C3S), working on China’s foreign policy and domestic politics. His work has been published in The Diplomat, 9 Dash Line, East Asia Forum, ISDP & Tokyo Review, among others. He is also the Director of ORCA Consultancy.