Since Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, China has consistently framed its position through the lens of sovereignty and non-interference. Official rhetoric, such as Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian’s assertion that China will continue to play a constructive role for Myanmar’s peace and reconciliation process, projects an image of principled neutrality. Reiterating a “Myanmar-led, Myanmar-owned” resolution, Beijing has sought to align its stance with its long-standing doctrine of non-intervention. Yet, recent developments reveal how this posture is less grounded in normative commitments but more in pragmatic manoeuvring to safeguard core national interests.

In a revealing development that underscores the disjuncture between China’s stated foreign policy principles and its strategic behavior, Reuters reported that Beijing recently issued an ultimatum to the Kachin Independence Army (KIA): withdraw from Bhamo in northern Shan State or risk a suspension of rare earth mineral purchases. The KIA, one of Myanmar’s most prominent ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) operating near the China–Myanmar border, is currently engaged in protracted conflict with the Tatmadaw over territorial control. This episode is not an anomaly/isolated incident, as China has consistently pressured EAOs to de-escalate offensives against the junta under the pretext of maintaining border stability. However, such actions, in practice, serve to reinforce the military regime’s capacity to suppress resistance forces. This pattern exposes the limits of Beijing’s professed policy of non-interference and casts doubt on its claims to uphold sovereignty and territorial integrity in principle. Instead, it reveals a calculus of selective engagement driven by geoeconomic and geopolitical imperatives.

Official Narrative VS Strategic Reality in the Ground

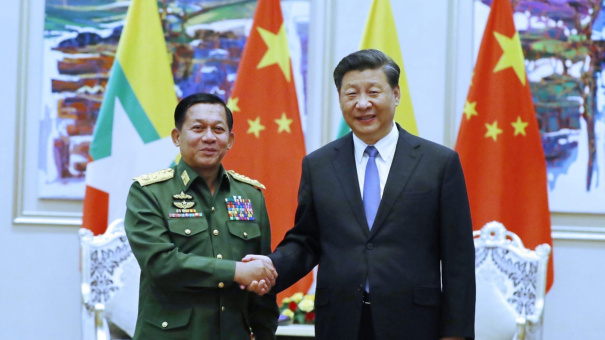

When Xi Jinping met with General Min Aung Hlaing in May 2025, he reaffirmed China’s intention to deepen ties with Myanmar under the banner of building a “community of shared future,” while reiterating the core principles of the Global Security Initiative (GSI) . According to statements, the GSI stresses respect for national sovereignty and territorial integrity, and explicitly opposes interference in the internal affairs of other countries. Meanwhile, the Community of Shared Future emphasizes universal values such as peace, development, equity, justice, democracy, and freedom. However, China's conduct in Myanmar reveals a clear gap between its normative rhetoric and strategic practice.

While China publicly espouses a stance of neutrality and peacebuilding in Myanmar’s political crisis, its actions on the ground point to a more calculated and strategically driven engagement. Since late 2024, Beijing has portrayed itself as a mediator between the military junta and EAOs in pursuit of regional stability. However, this mediation role increasingly appears to serve China’s own geopolitical and security interests rather than facilitating a balanced resolution.

Multiple reports indicate that Chinese authorities have systematically pressured EAOs to cease their movement and indirectly facilitated the Tatmadaw’s territorial resurgence. This strategy has gone beyond diplomatic persuasion. For instance, Chinese authorities in Yunnan placed Peng Dexun, the leader of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), under house arrest after the group refused to engage in negotiations with the junta. Additionally, Chinese officials imposed economic coercion by halting the flow of essential goods, including medicine and electricity, into MNDAA-held areas. These concerted measures have forced the MNDAA to enter negotiations and eventually surrender control of Lashio township to the Tatmadaw without armed resistance. Strikingly, Chinese security personnel were reported to have overseen the handover, underscoring Beijing’s direct operational involvement and raising critical questions about China’s role in shaping the conflict’s trajectory.

China’s willingness to intervene so overtly in northern Myanmar stems from two key strategic calculations. First, instability in the region has triggered a surge in cross-border displacement and disrupted border trade, especially in cities like Ruili in Yunnan Province, posing economic and social risks on the Chinese side. Second, Beijing views the Tatmadaw as a more dependent and pliable partner than the EAOs. While ethnic groups retain some leverage and autonomy, the junta is far more reliant on Chinese political cover and economic engagement, making it more likely to accommodate Beijing’s demands.

A significant pattern in Myanmar’s ongoing peace dynamics is the consistent alignment of negotiation outcomes with Beijing’s strategic interests. Though China’s role in promoting regional stability is expected given its geographic proximity and economic ties, what is increasingly concerning is its expanding role not merely as a facilitator of dialogue, but as a gatekeeper of participation and a broker of outcomes. In 2024, for instance, China excluded key democratic actors like the NUG, while pressuring EAOs such as the MNDAA and TNLA into submission through economic coercion and political detention.

Strikingly, the outcomes of the last five China-brokered mediation rounds have consistently aligned with Chinese interests. These include securing guarantees for the safety of Chinese nationals and investments, reinforcing border stability, and obtaining commitments from EAOs to retreat from strategic zones. On the junta’s side, China has secured promises to fast-track BRI projects and expand its strategic footprint, evident in developments such as the reported establishment of a Chinese private military company in Myanmar. The ceasefire agreements emerging from these talks have not aimed to address the root causes of the conflict, but rather to preserve a narrow version of ‘stability’ - one that protects China’s infrastructure, trade routes, and regional influence.

Myanmar as a Litmus Test for China’s Global Vision

Myanmar has become a revealing case study for evaluating the credibility and coherence of China’s global initiative, particularly its promotion of the GSI and Community of Shared Future. Despite officially advocating for dialogue and non-interference, China has continued high-level diplomatic ties with the junta, supported at global forums like the United Nations, and allowed the flow of arms, military equipment, and surveillance technologies into Junta’s hands. At the same time, Beijing has avoided applying any meaningful pressure on the junta to negotiate with opposition actors or EAOs. This reveals a clear strategic calculus: when core geopolitical and economic interests are at stake, China subordinates normative principles to the logic of realpolitik.

Concurrently, the contradiction becomes even starker as China’s vision of building a 'Community with a Shared Future for Mankind' rings increasingly hollow in light of its continued support for a regime credibly accused of systemic atrocities. While Beijing champions “win-win cooperation” as the bedrock of its global partnerships, its sustained engagement with Myanmar’s military junta, an internationally condemned and isolated actor, effectively grants legitimacy to a government lacking both democratic mandate and human rights credibility. This suggests that inclusion in China’s envisioned global community hinges not on shared values or normative commitments, but on strategic alignment to Beijing’s geopolitical priorities. Such an approach undermines the normative integrity of China’s global initiatives and exposes a widening gap between its stated principles and actual behavior.

Myanmar, in this context, serves as a litmus test - one that reveals the disconnect between the ideals of initiatives like the GSI and the Community of Shared Future, and the interest-driven, realpolitik decisions Beijing makes on the ground. This disconnect is not merely rhetorical; it carries significant political implications. First, as China’s global influence expands, the pressing question is not just whether it will reshape the international order, but how and with what values at its core. The Myanmar case projects that the values underpinning China’s global vision may be less about inclusive peace and cooperative development, and more about selective, strategic pragmatism. Second, while China’s support for the Myanmar military may secure short-term objectives, such as border stability, resource access, and the uninterrupted advancement of BRI projects, it simultaneously risks contributing to long-term regional instability. Finally, although Beijing positions itself as a champion of a more just, inclusive, and multipolar global order, particularly in the Global South, its approach in Myanmar reveals the conditional and transactional nature of this vision. Rather than embodying principled leadership, China’s behavior reflects a pattern of situational alignment, reinforcing the perception that its global commitments are shaped more by geopolitical expediency than by genuine adherence to the values it proclaims.

Image Credit: Katehon

Author

Ophelia Yumlembam

Ophelia Yumlembam is a Junior Research Associate at the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). Before joining ORCA, she worked at the Dept. Of Political Science, University of Delhi, and interned at the Council for Strategic and Defence Research in New Delhi. She graduated with an M.A. in Political Science from the DU in 2023. Ophelia focuses on security and strategic-related developments in Myanmar, India's Act East Policy, India-Myanmar relations, and drugs and arms trafficking in India’s North Eastern Region. Her writings have been featured in the Diplomat, South Asian Voices (Stimson Centre), 9dashline, Observer Research Foundation, among other platforms.