Click here to view the full map.

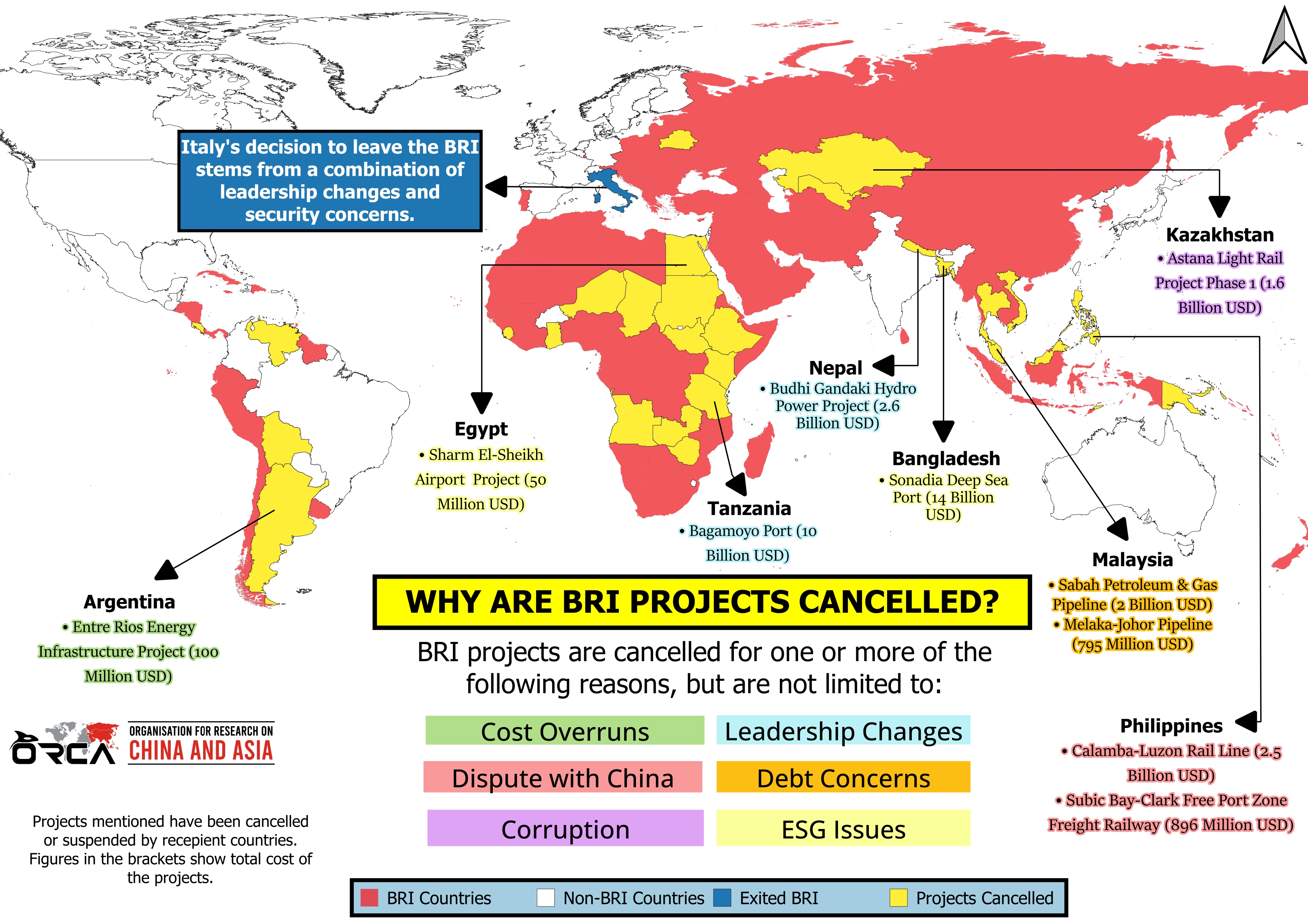

As Italy officially becomes the first country to exit the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), questions about the future of China’s signature foreign policy initiative have reemerged. Italy’s exit closely followed an announcement by the Philippines to cancel three BRI projects with China. The decision by the Philippines was possibly a reaction to Beijing’s aggressive strategies in the South China Sea (SCS), as well as the growing unviability of these projects. With this, objections and opposition to the BRI have begun to translate into concrete action, as also evident from declining participation of heads of state at BRI forums. The recent Belt and Road Forum witnessed the participation of only 23 heads of state, whereas the previous two editions had seen 30 and 37 heads of state participating in 2017 and 2019 respectively. The AidData report suggests that over 18 billion USD worth of projects were cancelled between 2013-2021 in BRI countries and funded by China. This is indicative of the waning interest in the BRI, and intensifies the debate on factors responsible for cancellation of projects. What factors motivate the cancellation of BRI projects?

BRI projects are cancelled or suspended for one, or a combination, of the following key reasons:

- Cost Overruns: Large infrastructure projects have often been delayed or stalled due to cost complications in the initial stages of the project. Cost overruns are a function of difficulties in land acquisition, conducting feasibility studies and impact assessments which disrupt the project timeline and inflate costs. Costs also increase due to budgetary constraints, corruption and other irregularities in the recipient country, as well as international trade factors. For instance, a gas infrastructure project in Argentina’s Entre rios province could not be implemented due to high cost of items such as insurance that increased the financial value of Chinese loan of 100 million USD.

- Leadership Changes: The turnover of political leadership, as a result of elections or otherwise, has often resulted in the cancellation or renegotiation of BRI projects initiated by the previous government/administration. In recent years, China has emerged as a subject of political debate in countries where it has a large BRI presence. Italy’s decision to leave the BRI was largely a result of a change in political leadership: the arrival of Giorgia Meloni as Prime Minister in Italy resulted in a termination of Italy's BRI MoU with China. Similarly, in Nepal, the Budhi Gandaki Hydro Power Project (2.6 Billion USD), originally approved by the K.P Oli government, was cancelled immediately after the arrival of the Deuba government in 2017.

- Disputes with China: Countries that have territorial disputes and other conflicts with China are likely to rethink their participation in the BRI. The most recent example is the Philippines, which has cancelled 3 BRI projects: Mindanao Commuter Rail Line (1.45 Billion USD), Calamba-Luzon Rail Line (2.5 Billion USD) and Subic Bay-Clark FreePort Zone Railway (896 Million USD), largely due to clashes with China in the SCS. Moreover, countries in ASEAN may also follow the example of the Philippines if China continues its assertion in SCS.

- Debt Concerns: A common reason for canceling BRI projects is the financial burden of loans extended by Chinese banks. For lower and middle income countries in the Global South, this is a major factor that drives their decision to rethink BRI projects. For instance, in Malaysia, the Sabah Petroleum & Gas Pipeline (2 Billion USD) and the Melaka Johor Pipeline project (795 Million USD) were cancelled for their overwhelming potential debt burden.

- ESG Issues: BRI projects have been impacted by environmental, social and governance (ESG) challenges. Projects like hydropower plants or ports in environmentally sensitive regions have often become a cause of protests and other political pressures in recipient countries. These projects are also criticized for poor environment impact assessments, coupled with corruption at local and national level. For instance, the Sonadia Deep Sea Port project in Bangladesh was cancelled to protect the marine environment of the Bay of Bengal. In Egypt, the Sharm El-Sheikh International Airport was cancelled because of a policy change by the government because the government decided to allocate the funding for community development programs with a wider social impact.

- Corruption: Large infrastructure projects typically involve bribes given to local and central governmental authorities to facilitate project development. Corruption and related irregularities have emerged as a commonly cited reason for the cancellation of BRI projects. In Kazakhstan, the Astana Light Rail project was cancelled after reports of irregularities emerged – 258 Million USD of the 313 Million USD provided by China had been wrongfully deposited in the Astana Banki, which defaulted in late 2018.

For the Philippines, its exit was motivated by China’s aggressive posture in the SCS and for Italy, it was the lack of financial benefits, coupled with external pressure from other non-BRI countries. The case of Italy and Philippines demonstrates the discontent of partner countries with China’s BRI. This has created an opening for non-China providers of connectivity infrastructure to emerge as suitable alternatives that can offer greater transparency, sustainability, and reduced risk, setting them apart from the BRI. The cancellation of BRI projects for the reasons outlined above, along with other factors, may cause other BRI participants to reassess their involvement in the initiative.

How can non-Chinese alternatives to the BRI enhance their appeal as providers of connectivity infrastructure?

- Sector targeting and smaller, more effective initiatives: In the 10 years of the BRI’s existence, it has incorporated several domains within its purview, ranging from connectivity infrastructure, digital connectivity to energy infrastructure. Initiatives created to counter BRI cannot attempt to operate in all domains of connectivity infrastructure, and instead must focus on specific aspects of connectivity. For instance, Japan and EU’s Green Alliance, ideated to advance their sustainable infrastructure goals by collaborating on energy transition and innovation, is focused purely on energy connectivity. Similarly, JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) and India have focused their resources to develop road and port infrastructure in Bangladesh, building on their expertise in construction of road infrastructure in India’s North-East.

- Highlight USPs of non-Chinese alternatives: Compared to China, non-BRI initiatives have showcased a desire to promote greater transparency, greater willingness to undertake environmental and social impact assessments, and engaged in consultations with community stakeholders in project locations. For instance, JICA projects in India and Bangladesh have conducted and published extensive surveys and consultations with communities in and around the project location. Non-China alternatives should highlight such strengths in adopting a more consultative and transparent approach to project development, attracting the interest of countries keen to avoid public backlash for violating ESG norms.

- Focus on cancelled/suspended/troubled projects: BRI projects cancelled by recipient countries have not been taken up by non-China initiatives. Initiatives like the B3W (Build Back Better World), BDN (Blue Dot Network), Global Gateway, PGII (Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment), EPQI (Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure), Platform for India-Japan Business Cooperation in Asia-Africa (formerly Asia-Africa Growth Corridor) and even the Quad, which have branded themselves as ‘alternatives’, have failed to spot the opportunity created by China’s exit from infrastructure projects. These initiatives could build their credibility by offering competitive financing terms, better quality, and strict adherence to timelines for projects abandoned by China. Moreover, the reasons for cancellation of BRI projects could be taken into account by non-China initiatives to identify areas wherein they can outcompete the BRI. Furthermore, these initiatives need to have similar quality standards, procurement practices, incentives and risk-mitigation measures to increase their attractiveness to developing countries.

- Implementation: Non-Chinese initiatives have limited their participation to the financing of connectivity projects and have little to no presence in the project construction space. This leaves Chinese contractors to set international standards for railways, ports, and other key connectivity projects. To counter this, Japan had launched Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI) in 2015, with an original budget of 110 billion USD and later increased to 200 billion USD in 2016. The main objective of this initiative was to replace Chinese standards in infrastructure by raising quality standards. It also focused on attracting private funds and private companies as opposed to China’s state-led financing. Similarly, G20’s Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment (PQII) needs to be strongly backed by financial avenues such as the QII partnership which has approved 229 grants in 2023 worth 64.1 million USD which has helped include QII principles in World Bank-run projects worth over 50 billion USD.. This needs to increase exponentially in the coming years as it also assists developing countries achieve SDGs.

Despite the setbacks the BRI has faced, it addresses the immediate and unmet need for infrastructure development and investment in the developing world. Therefore, to emerge as a possible alternative to the BRI, measures mentioned above need to be taken into account to leverage discontent created against China’s BRI, and countries including the US, Japan, India, EU have to take swift measures to fill the gap created by cancelled BRI projects.

Author

Team ORCA

Combined works by various researchers at ORCA