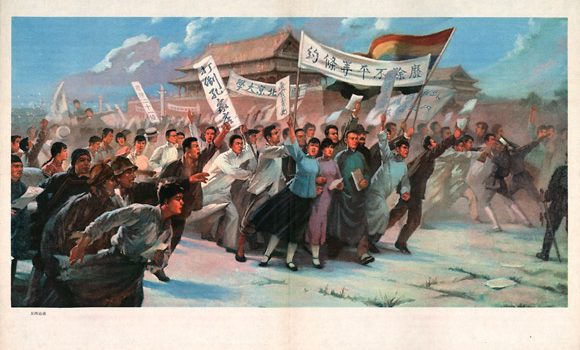

The May Fourth Movement —which originated in 1916, peaked in 1919 and ended in 1921— was one of the most monumental intellectual revolutions and socio-political reform movements in China’s history. Chinese students and intellectuals rallied to protest against the country’s continued international subjugation –part of the Century of Humiliation —by the Western powers and more specifically, Japan. It has been a public holiday since 1949, and remains an important symbol of nationalistic patriotism in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), celebrated across China as Youth Day.

In recent years, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has given special focus to the relevance of the May Fourth Movement, and Chinese President Xi Jinping has regularly invoked its sentiments when addressing his hopes for China’s future —and more specifically, that of its youth — in the world. Through official documents and statements, the CPC has further sought to demonstrate how the May Fourth Movement of 1919 continues to be relevant in today’s China. Why does the May Fourth Movement —-which arguably started the modern Chinese tradition of student protests— hold such relevance till date, especially when the Party is notorious in its contempt for most examples of student activism?

Legacy well beyond its centennial

Many present day Chinese political diktats and goals continue to borrow from the May Fourth Movement. The movement articulated contempt for traditional Chinese culture by the country’s intellectuals, and its leaders Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi played key roles in shaping China as we know today. The former went on to become a founder of the CPC itself in 1921 while the latter initiated the baihua vernacular writing style that replaced the two thousand year old traditional Chinese language. The legacy of the movement in its immediate aftermath was carried forward by Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong as well; they both were participants of May Fourth. Later on, the bifurcation in how both drew from the movement highlights how the central goal of May Fourth was — and continues to be —retained even as its implementation is altered by Chinese leaders to support their own purposes. For instance, while Chiang did not turn away from Confucian values as a whole, he used self-correction as a means to herald the New Life Movement that ultimately sought to rebuild the “essence” of what being Chinese meant. Mao’s writing in the 1930’s highlighted “borrowing but preserving”; as a strong critic of traditional Chinese culture, he cautioned against forgetting one’s history while advocating for change hence stating that China’s Communist ideology must have Chinese characteristics.

Essentially, the May Fourth Movement continues to be seen as a key moment in China’s modern history, marking a turning point in the country’s cultural, political, and intellectual development. Firstly, the movement emphasized the need for China to modernize and catch up with the West, and its legacy can be seen in the Party’s emphasis on economic development, scientific innovation, and technological advancement. Additionally, the movement’s emphasis on nationalism and social responsibility can be seen in the CPC’s promotion of Chinese culture and its focus on poverty alleviation and social welfare. Secondly, the May Fourth Movement is closely tied to the development of the CPC. Many of the key figures of the movement, including Mao, Deng Xiaoping, and Zhou Enlai, went on to become prominent leaders of the CPC. The movement’s emphasis on democracy, nationalism, and social reform can be seen in the CPC’s early policies and ideology, including its promotion of agrarian reform, women’s rights, and proletarian revolution. Thirdly, the May Fourth Movement continues to be an important source of cultural and intellectual inspiration in contemporary China. The movement’s emphasis on individualism, free thought, and cultural creativity has been influential in the development of China’s art, literature, and cultural industries. The movement’s legacy can also be seen in China’s contemporary social and political debates, including discussions of democracy, human rights, and political reform.

However, it should be noted that the CPC’s interpretation of the May Fourth Movement has been highly selective and sanitized. While the party has promoted certain aspects of the movement’s legacy, such as its emphasis on national unity and social progress, it has largely ignored or suppressed the movement’s more radical and democratic elements. Over the past decade, the government has also further tightened control over civil society and the media, limiting opportunities for open discussion and debate about the movement’s legacy and its relevance to contemporary China.

May Fourth in Xi’s Leadership

Xi Jinping has made several references to the movement in his speeches and writings, and it is clear that he sees it as a source of inspiration for his vision of China’s future. One of the key themes of the May Fourth Movement was the need for China to become strong and modern in order to resist foreign domination. This idea resonates strongly with Xi’s emphasis on China’s rejuvenation and the “Chinese Dream,” which he has defined as the goal of making China a strong, prosperous, and modern country by the middle of the 21st century.

Hence, Xi’s inculcation of May Fourth is similar to Chiang and Mao’s interpretation of the movement, wherein while continuing the move towards modernization of thought, the leaders ultimately laid main emphasis on proud identity creation of the Chinese peoples. This was the driving force behind the May Fourth revolution’s fight against imperialism, and it is this focus that we see under Xi’s leadership as well via “socialism with Chinese characteristics”; modernization drives for the country and the military; and the ‘Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation’ via which he urges the youth to “dare to dream” . Xi has incorporated the May Fourth Movement into his domestic governance in several ways, of which education is an important example. His efforts to ensure deeper study of the spirit of the May Fourth movement to inculcate the same in the youth of contemporary China so as to achieve the China Dream were first made in 2015 when it was incorporated into the national education system. This has led to a renewed emphasis on teaching the history and values of the May Fourth Movement in Chinese schools, as well as the promotion of extracurricular activities that promote the movement’s ideals.

Xi has also emphasized the importance of Chinese culture and identity, which is another key aspect of the May Fourth Movement. The movement was characterized by a rejection of traditional Chinese culture and a call for the adoption of Western ideas, but it also emphasized the need to preserve and promote Chinese culture in the face of foreign influence. Xi has similarly called for a revitalization of traditional Chinese culture, and on October 16, 2022, he has promoted the idea of “cultural confidence” as a way of strengthening China’s soft power. Herein, cultural policy has emerged as a key area of May Fourth appropriation. This has included the development of museums, cultural centers, cultural films and literary anecdotes as well as other institutions dedicated to preserving and promoting China’s cultural heritage drawing from the values of the May Fourth Movement. A prominent example here is that of the continued celebration of the works of Lu Xun, recognized as “one of the greatest figure(s) in 20th-century Chinese literature”.

Another important aspect of the May Fourth Movement was its emphasis on democracy and political reform. Although the movement did not ultimately succeed in bringing about major political change in China, it helped to lay the groundwork for the CPC’s rise to power. Xi has also emphasized the need for political reform, but he has done so in a way that emphasizes the importance of maintaining stability and the leadership of the Communist Party. Democratic Centralism, in principle, has been the accepted “fundamental organizational principle” of the Party; it has drawn greatly from the May Fourth movements doctrines. Hence, political discourse and reform continues to emphasize the importance of stability and the leadership of the Communist Party, even as it dovetails into May Fourth ideals.

May Fourth: Why no threat perception?

The CPC has maintained its control on Chinese historical legacies. For instance, while the study of May Fourth is encouraged — as its interpretation has been successfully sanitised — June Fourth (referring to Tiananmen Square, 1989) remains categorised as “anti-Party, anti-socialism activities”. Amidst China’s taut history with student revolutions and protests, it is unlikely that the May Fourth Movement would emerge as a direct threat to Xi Jinping and his regime with regards to a student revolution. Its ideals and values have been incorporated well into the official discourse and the education system in China. While some elements of the movement’s legacy, such as its emphasis on democracy and political reform, could be seen as potentially challenging to the current government, it is unlikely that mention of the movement would result in a widespread student revolution.

The government maintains a powerful propaganda machine that promotes its own vision of Chinese history and culture, which includes a sanitized version of the May Fourth Movement that emphasizes patriotism and social responsibility, but downplays its more radical and democratic elements. Furthermore, the Chinese government has shown a willingness to use force to suppress dissent and protests as was demonstrated in 1989 during the Tiananmen Square protests. Since then, the government has taken steps to prevent the emergence of similar movements and has invested heavily in its security apparatus to ensure that dissent is kept under control.

In summary, while the May Fourth Movement’s ideals and values may hold some potential for challenging the current government’s policies and actions, it is unlikely that the movement itself would emerge as a direct threat to Xi Jinping and his regime with regards to a student revolution. The government’s strict control over civil society and political dissent, along with its willingness to use force to suppress protests, would likely prevent the movement from gaining widespread traction or resulting in significant political change.

Overall, the May Fourth Movement holds significant symbolic and ideological importance for Xi Jinping’s vision of China’s future. It represents a call for modernization, national strength, cultural confidence, and political reform, all of which are key components of Xi’s broader agenda for China’s development. Xi has incorporated the May Fourth Movement into his domestic governance in a way that emphasizes the importance of patriotism, innovation, social responsibility, and cultural confidence. By promoting these values, Xi hopes to strengthen China’s national identity and promote its development as a modern, prosperous, and influential country, signalling that the continued legacy of May Fourth will thrive.

Author

Eerishika Pankaj

Eerishika Pankaj is the Director of New Delhi based think-tank, the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA), which focuses on decoding domestic Chinese politics and its impact on Beijing’s foreign policymaking. She is also an Editorial and Research Assistant to the Series Editor for Routledge Series on Think Asia; a Young Leader in the 2020 cohort of the Pacific Forum’s Young Leaders Program; a Commissioning Editor with E-International Relations for their Political Economy section; a Member of the Indo-Pacific Circle and a Council Member of the WICCI’s India-EU Business Council. Primarily a China and East Asia scholar, her research focuses on Chinese elite/party politics, the India-China border, water and power politics in the Himalayas, Tibet, the Indo-Pacific and India’s bilateral ties with Europe and Asia. In 2023, she was selected as an Emerging Quad Think Tank Leader, an initiative of the U.S. State Department’s Leaders Lead on Demand program. Eerishika is the co-editor of the book 'The Future of Indian Diplomacy: Exploring Multidisciplinary Lenses' and of the Special Issues on 'The Dalai Lama’s Succession: Strategic Realities of the Tibet Question' as well as 'Building the Future of EU-India Strategic Partnership'. She can be reached on [email protected]