China’s expanding role as a mediator in the Thailand–Cambodia conflict signals a deliberate shift in its regional diplomacy—away from passive involvement and towards active conflict management. Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent trilateral meeting with his Thai and Cambodian counterparts marks not merely a diplomatic gesture, but a strategic intervention aimed at embedding China into Asia’s conflict resolution architecture.

Beijing’s previous involvement in Saudi Arabia-Iran détente as well as its recent attempts to normalise Pakistan-Afghanistan ties have already highlighted its willingness to institutionalise mediation as a key foreign policy tool. The ongoing Thai-Cambodia border conflict further offers China an opportunity to project its image as a neutral facilitator committed to peace and dialogue.

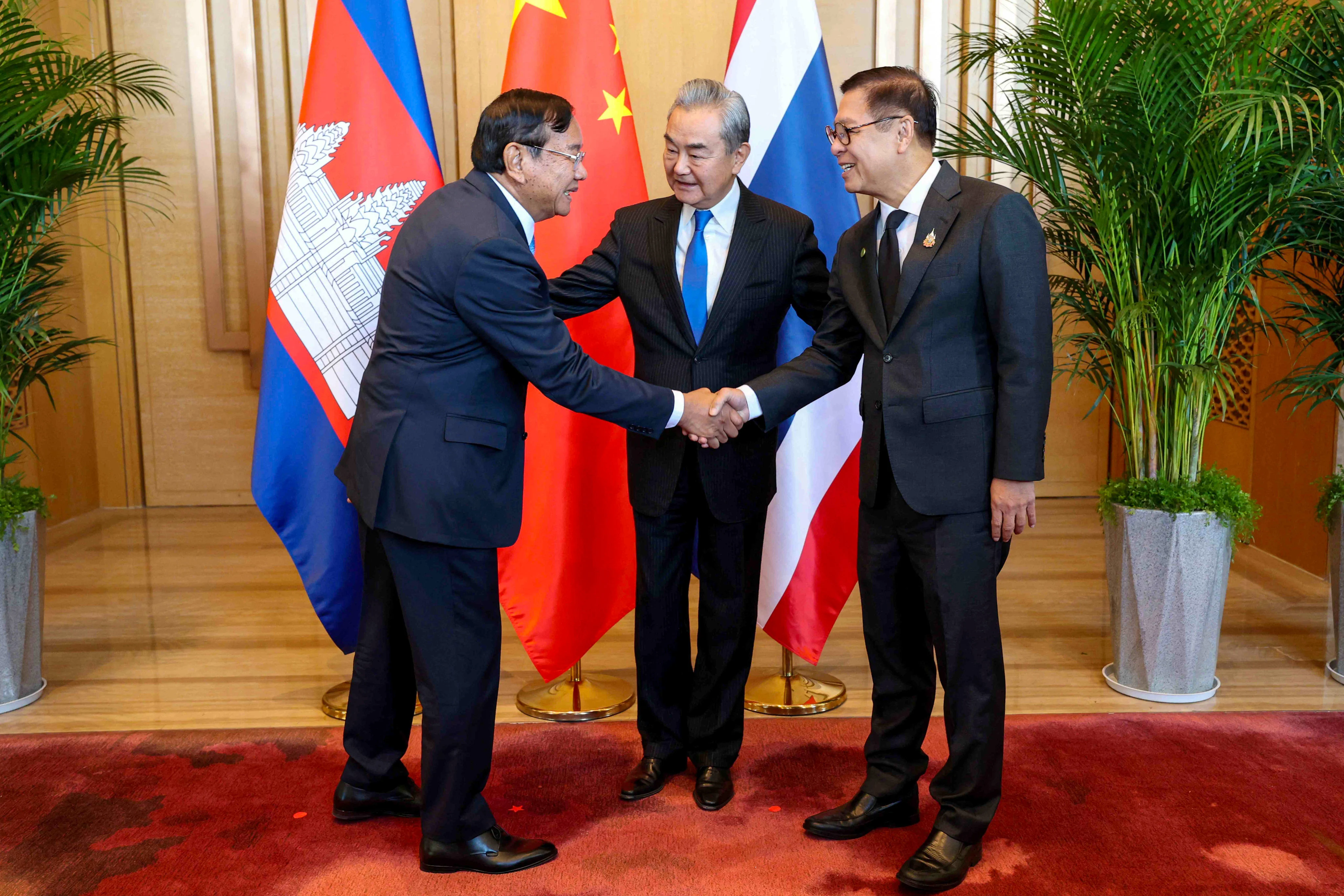

Yet, China’s mediation strategy has not followed a linear trajectory, but has rather evolved over the months since the conflict began in July 2025. During the early days of the crisis, China framed its involvement as complementary to the “ASEAN Way”, focusing on the ASEAN centrality principle. However, with the failure of ASEAN-led ceasefire efforts in early December as clashes renewed, it created a diplomatic opening that Beijing now attempts to occupy to strengthen its regional influence. By independently hosting the trilateral meeting in Yunnan immediately after the ceasefire, China positions itself not only as a supporter of existing security frameworks in Southeast Asia, but also as an alternative stabilizing power capable of managing regional conflicts through diplomacy.

Preserving Regional Economic and Security Interests

China’s mediation efforts in the Thailand–Cambodia border conflict are mainly driven by its economic and security imperatives to prevent instability along a vital corridor for its regional dominance. Characterized by ‘building community with a shared future’ – one of the highest levels of partnerships in China’s diplomatic toolkit - both bilateral relations occupy pivotal positions in its Southeast Asian connectivity strategy. Thus, China does not view this conflict as a localised bilateral dispute, but as one carrying significant strategic implications for its regional interests.

Firstly, prolonged hostilities threaten to disrupt China’s supply chain networks in Southeast Asia affecting multiple sectors. For instance, China’s significant investments in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor, amounting to over 8.4 billion USD and spanning across electric vehicle, aviation and railway construction industries, are susceptible to sustained instability. Similarly, China’s efforts to implement Cambodia’s Fish and Rice Corridor as well as invest in its industrial development corridor may encounter risks if the ongoing conflict results in long-term political instability. The presence of a significant Chinese diaspora in both countries further raises the stakes, as seen in a recent incident involving a Chinese national who was injured due to cross-border attacks.

Secondly, China has also been grappling with transnational scam compounds operated by Chinese nationals from border regions of Thailand and Cambodia along with other Southeast Asian countries. Reiterating these concerns, Thailand has also increasingly framed its attacks on Cambodia as a part of its broader campaign against cross-border scam syndicates and cybercrime networks. These measures closely mirror Beijing’s own priorities, as Chinese authorities have intensified crackdown on Southeast Asian scam networks in the past few years. On the other hand, Cambodia’s recent extradition of Chen Zhi to China amidst border clashes also underscores Beijing’s urgency to control these illicit networks. However, prolonged border clashes can disrupt cross-border access potentially facilitating scam compounds to relocate, conceal operations and evade monitoring. It can further complicate China’s intelligence sharing and enforcement coordination with both countries which can have a direct impact on its domestic governance. Hence, maintaining stability between Southeast Asian countries remains critical for China to dismantle and deter these transnational criminal networks

In terms of China’s broader regional influence, its emphasis on the Asian Security Concept (亚洲安全观) implies that Asian security problems must be resolved by Asian actors through dialogue rather than external intervention. Thus, failure to contribute meaningfully to restoring political stability in Southeast Asia may weaken this narrative. Conversely, even partial success allows Beijing to claim the success of its mediation model as capable of reducing tensions without resorting to coercion or alliance politics. In this context, China’s shuttle diplomacy - led by its Special Envoy for Asian Affairs, Deng Xijun - has not only emphasised maintaining ceasefires but also at reinforcing Beijing’s normative claims about how regional security should be managed.

Counterbalancing US Engagements

China’s involvement in the crisis fits into a wider pattern of diplomatic outreach that extends beyond Southeast Asia. In recent years, Beijing has increasingly presented itself as a mediator in conflicts where Western influence is contested or limited. Beijing’s mediation efforts are therefore crucial in the context of its strategic competition with the US. Alongside China, Washington has also remained actively engaged in encouraging ceasefire and stabilisation between Thailand and Cambodia. Recently, Washington announced a $45 million USD aid package aimed at bolstering the fragile ceasefire, supporting border stabilisation, demining and humanitarian needs, thereby signalling continued US involvement in Southeast Asian peacebuilding. This move follows previous high-profile involvement by the US — including President Trump’s diplomatic intervention — which helped secure an initial ceasefire agreement, widely touted as ‘Kuala Lumpur Peace Accords’.

Beijing, on the other hand, has adopted a relatively restrained position, emphasising continuous communication and primacy of regional processes over high-visibility political interventions. Beijing’s mediation is framed as supportive of ASEAN as the primary actor and avoiding explicit conditions or linkage to economic incentives. This contrast is not accidental; it allows Beijing to position its mediation model as normatively aligning with ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation which emphasises sovereignty and non-interference.

Mediation thus becomes a domain of strategic competition, not through force projection but through agenda-setting and norm shaping. By embedding itself in the crisis management process, Beijing limits the space for the US to shape outcomes unilaterally or claim exclusive credit for dispute resolution. At the global level, such engagements also enable China to sustain its agency in great power rivalry by asserting its influence in the neighbourhood, particularly as the new US National Security Strategy challenges Beijing’s role in the Western hemisphere.

Limits of Mediation with Chinese Characteristics

Nonetheless, the Thailand–Cambodia case also reveals the limits of China’s mediation strategy. Despite projecting neutrality, China has emerged as a major weapons supplier to both Thailand and Cambodia. Thai forces have repeatedly claimed seizing China-made weapons including anti-tank missiles, grenade launchers and more on the Cambodian side. At the same time, despite being a major ally of the US, Thailand has significantly expanded the purchase of Chinese weapons systems in the past few years, including a recent procurement deal with a Chinese State-owned Enterprise Norinco for armoured vehicles. This contradiction raises questions about China’s neutrality, as it continues to supply weapons while simultaneously positioning itself as a mediator for peaceful resolution. Despite the claims made by Chinese officials that arms trade with these countries is unrelated to the border conflict, such rhetorics do little to dispel perceptions that Beijing benefits from maintaining a degree of controlled instability.

More importantly, China’s conflict management tactics reveal that while they can facilitate dialogue and reduce immediate escalation risks, they are unable to envision and enforce structural solutions to deeply rooted disputes. Territorial conflicts driven by historical grievances and domestic political dynamics, such as the case of Thailand-Cambodia tensions, are often resistant to externally brokered compromises. Until now, Beijing has shown little inclination to pursue legal adjudication or enforceable boundary mechanisms - a pattern consistent with the approach to its own unresolved border disputes. In such a scenario, repeated allegations of ceasefire violations by Thailand or Cambodia will continue to underscore the fragility of agreements reached through China’s diplomatic influence.

Similarly, amidst Beijing’s involvement as a stabilising force, Southeast Asian states will continue to hedge by engaging multiple partners, including the US and ASEAN institutions, thereby diluting the long-term effectiveness of China’s mediation efforts. Thus, the Thailand–Cambodia conflict reveals the underlying principle of Chinese mediation: Beijing is willing to invest political capital in managing regional crises, but hesitates to assume the risks associated with engaging in structural solutions or long-term guarantees.

This crisis thus serves as a test case for China’s emerging mediation model—one that reflects its growing diplomatic confidence, but also reveals its structural limitations. It demonstrates how mediation allows China to expand its diplomatic footprint and project normative influence while maintaining strategic adaptability. Whether this model can deliver lasting results for Beijing remains uncertain, but its growing prominence suggests that mediation will remain central to China’s foreign policy toolkit in the years ahead.

Image Credit: Agence Kampuchea Press

Author

Omkar Bhole

Omkar Bhole is a Senior Research Associate at the Organisation for Research on China and Asia (ORCA). He has studied Chinese language up to HSK4 and completed Masters in China Studies from Somaiya University, Mumbai. He has previously worked as a Chinese language instructor in Mumbai and Pune. His research interests are India’s neighbourhood policy, China’s foreign policy in South Asia, economic transformation and current dynamics of Chinese economy and its domestic politics. He was previously associated with the Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS) and What China Reads. He has also presented papers at several conferences on China. Omkar is currently working on understanding China’s Digital Yuan initiative and its implications for the South Asian region including India. He can be reached at [email protected] and @bhole_omkar on Twitter.